(Coleoptera: Oedemeridae)

Issue No. 259

Ross H. Arnett, Jr.

March, 1984

Introduction

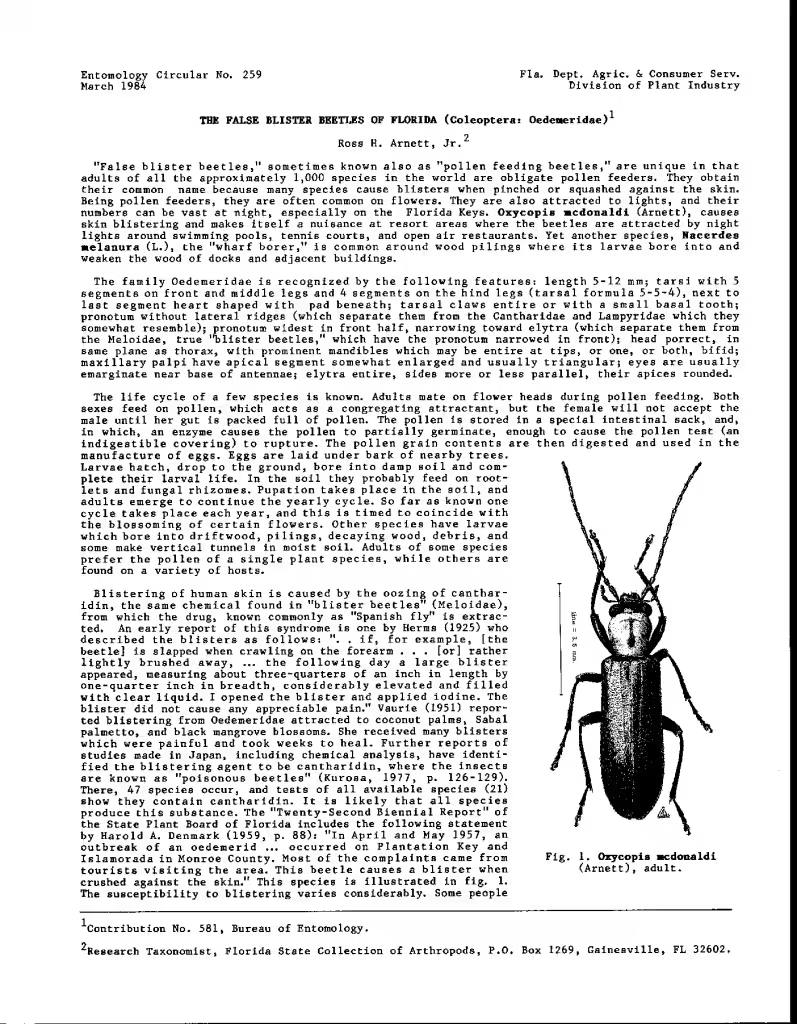

“False blister beetles,” sometimes known also as “pollen feeding beetles,” are unique in that adults of all the approximately 1,000 species in the world are obligate pollen feeders. They obtain their common name because many species cause blisters when pinched or squashed against the skin. Being pollen feeders, they are often common on flowers. They are also attracted to lights, and their numbers can be vast at night, especially on the Florida Keys. Oxycopis mcdonaldi (Arnett), causes skin blistering and makes itself a nuisance at resort areas where the beetles are attracted by night lights around swimming pools, tennis courts, and open air restaurants. Yet another species, Nacerdes melanura (L.), the “wharf borer,” is common around wood pilings where its larvae bore into and weaken the wood of docks and adjacent buildings.

The family Oedemeridae is recognized by the following features: length 5-12 mm; tarsi with 5 segments on front and middle legs and 4 segments on the hind legs (tarsal formula 5-5-4), next to last segment heart shaped with pad beneath; tarsal claws entire or with a small basal tooth; pronotum without lateral ridges (which separate them from the Cantharidae and Lampyridae which they somewhat resemble); pronotum widest in front half, narrowing toward elytra (which separate them from the Meloidae, true “blister beetles,” which have the pronotum narrowed in front); head porrect, in same plane as thorax, with prominent mandibles which may be entire at tips, or one, or both, bifid; maxillary palpi have apical segment somewhat enlarged and usually triangular; eyes are usually emarginate near base of antennae; elytra entire, sides more or less parallel, their apices rounded.

The life cycle of a few species is known. Adults mate on flower heads during pollen feeding. Both sexes feed on pollen, which acts as a congregating attractant, but the female will not accept the male until her gut is packed full of pollen. The pollen is stored in a special intestinal sack, and, in which, an enzyme causes the pollen to partially germinate, enough to cause the pollen test (an indigestible covering) to rupture. The pollen grain contents are then digested and used in the manufacture of eggs. Eggs are laid under bark of nearby trees. Larvae hatch, drop to the ground, bore into damp soil and complete their larval life. In the soil they probably feed on rootlets and fungal rhizomes. Pupation takes place in the soil, and adults emerge to continue the yearly cycle. So far as known one cycle takes place each year, and this is timed to coincide with the blossoming of certain flowers. Other species have larvae which bore into driftwood, pilings, decaying wood, debris, and some make vertical tunnels in moist soil. Adults of some species prefer the pollen of a single plant species, while others are found on a variety of hosts.

Blistering of human skin is caused by the oozing of cantharidin, the same chemical found in “blister beetles” (Me loidae), from which the drug, known commonly as “Spanish fly” is extracted. An early report of this syndrome is one by Herms (1925) who described the blisters as follows: ” .. if, for example, [the beetle] is slapped when crawling on the forearm … [or] rather lightly brushed away, … the following day a large blister appeared, measuring about three-quarters of an inch in length by one-quarter inch in breadth, considerably elevated and filled with clear liquid. I opened the blister and applied iodine. The blister did not cause any appreciable pain.” Vaurie (1951) reported blistering from Oedemeridae attracted to coconut palms, Sabal palmetto, and black mangrove blossoms. She received many blisters which were painful and took weeks to heal. Further reports of studies made in Japan, including chemical analysis, have identified the blistering agent to be cantharidin, where the insects are known as “poisonous beetles” (Kurosa, 1977, p. 126-129). There, 47 species occur, and tests of all available species (21) show they contain cantharidin. It is likely that all species produce this substance. The “Twenty-Second Biennial Report” of the State Plant Board of Florida includes the following statement by Harold A. Denmark 0959, p. 88): “In April and May 1957, an outbreak of an oedemerid … occurred on Plantation Key and Islamorada in Monroe County. Most of the complaints came from tourists visiting the area. This beetle causes a blister when crushed against the skin.” This species is illustrated in fig. 1. The susceptibility to blistering varies considerably. Some people are extremely susceptible, while on the other hand, the author, who has collected these beetles for 40 years, has never been blistered!

Florida has 29 species of Oedemeridae assigned to 8 genera. These figures are interesting when compared to the oedemerid fauna of the West Indies, where, 33 species belonging to 7 genera occur. Of these species, 11 also occur in Florida. The following is a list of the species known or thought to breed in Florida, along with a brief account of their distribution and a list of the plants on which they have been taken.

A key to the New World genera may be found in Arnett (1961), and descriptions of most of the Nearctic species are in Arnett (1951). A checklist of the species known to occur in North America, including Central America and the West Indies, may be found in Arnett (1983). A key to the following genera and species is included after the bibliography on page 4.